In software development, there are numerous guidelines and observations referred to as laws or principles. While these are not strict formulas that hold universally in all situations, they provide important frameworks that influence the development process. These principles can significantly impact the productivity of organizations, teams, and individuals. It's valuable for anyone involved in software to be familiar with them.

Brooks’s Law

“Adding [human resources] to a late software project makes it later.”

Fred Brooks

Due to coordination costs, more developers added to a project don’t always increase productivity. This law highlights the risks of "throwing more people" at a delayed project without proper planning.

Besides, it is important to find a balance between a too-large team and a small team consisting of members wearing multiple hats.

Image, author: Nathan S. Collier

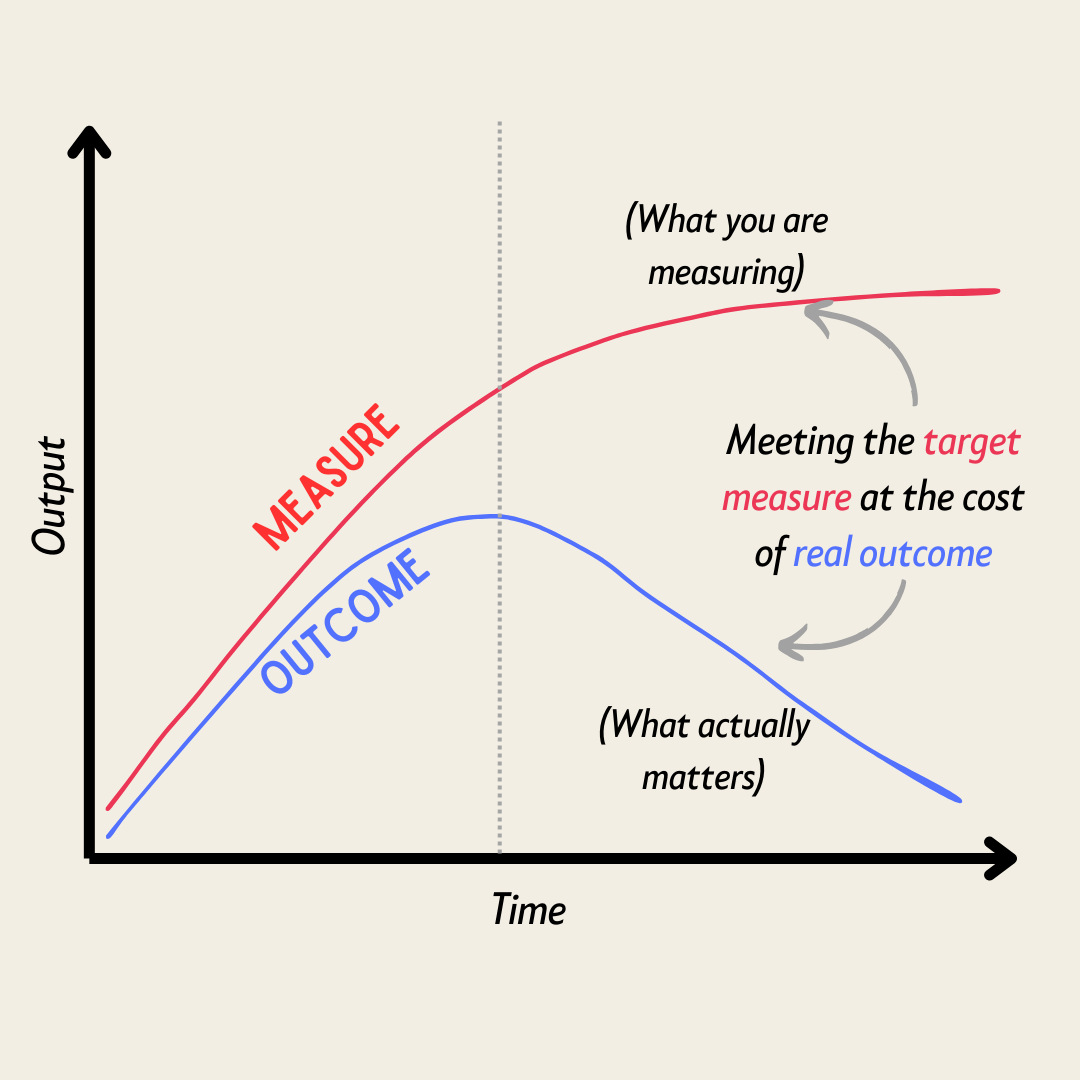

Goodhart’s Law

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Charles Goodhart

This means that once a specific metric is turned into a target or goal, people will start optimizing their behavior to meet that metric, often at the expense of the underlying goal it was meant to represent. We often aim for outcomes that are hard to quantify, and as a result, we rely on metrics that end up steering our efforts in directions we didn’t intend. It could be:

Number of lines of code (to measure productivity)

Story points completed per sprint (to measure team velocity)

Code coverage (to measure testing quality)

To avoid this trap we don’t have to abandon the data-driven approach. However, we need at least several metrics that drive our efforts. We have to constantly refine and reassess metrics, and in some cases don’t avoid qualitative approaches.

Image, author: Gaurav Jain

Hyrum’s Law

“With a sufficient number of users of an API, it does not matter what you promise in the contract: all observable behaviors of your system will be depended on by somebody.”

Hyrum Wright

As your API gains more users, people will start to rely on behaviors that weren’t intended or documented by the designers. Over time, even small, undocumented quirks or edge cases become "features" that users depend on, making changes or improvements to the API more complex without breaking something for someone.

This law highlights the challenges of maintaining backward compatibility and managing expectations as systems grow and evolve.

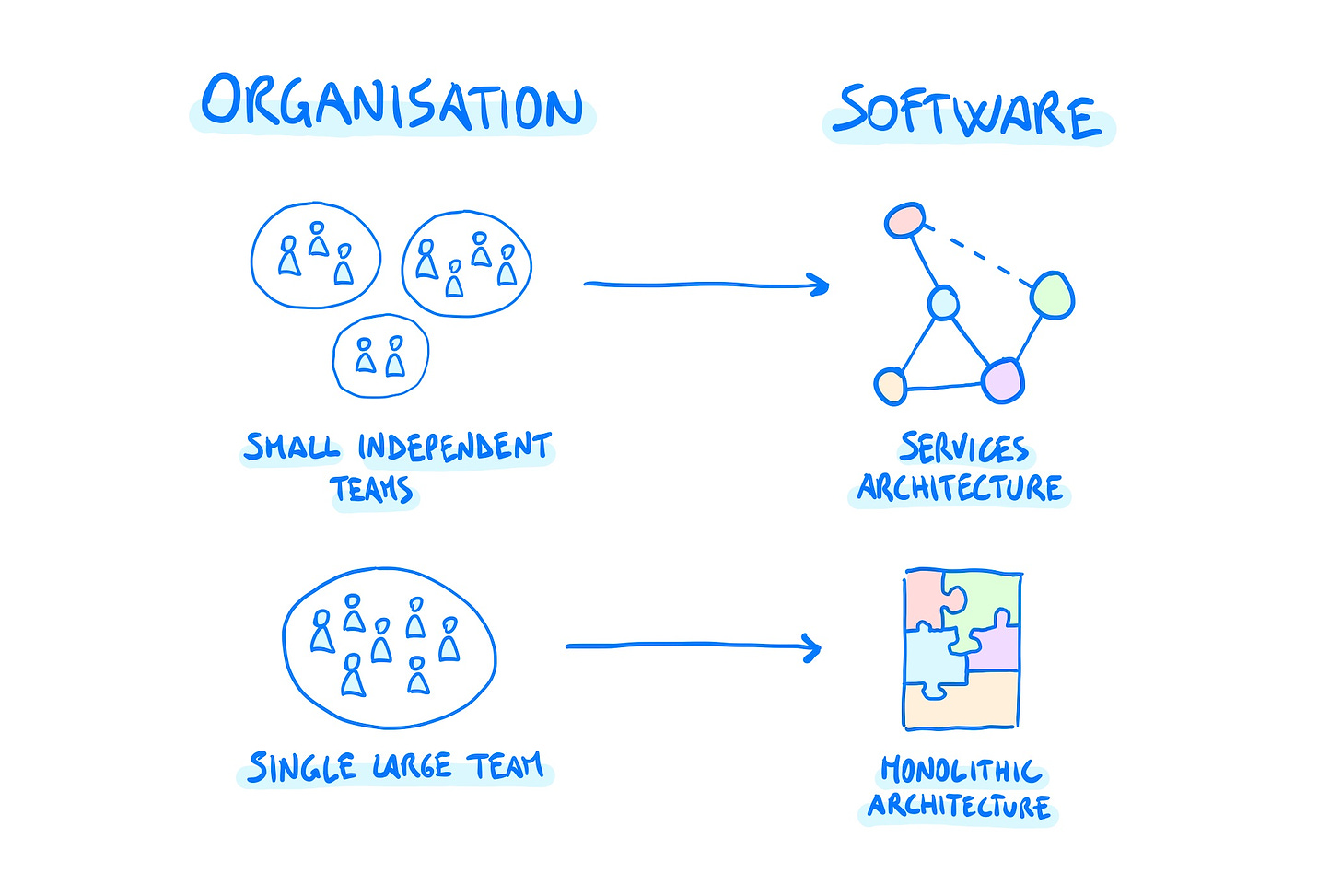

Conway’s Law

“Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.”

Melvin Conway

The structure of the software often mirrors the organizational structure that built it. If you blindly follow the existing team or department boundaries, you may end up with subdomains that are not well-aligned with the desired architecture or business capabilities.

The Inverse Conway Maneuver is the proactive application of Conway's Law. It suggests that if we want our software architecture to take on a specific shape or structure, we should first organize our teams and communication patterns to reflect that desired architecture.

Image, author: Luca Rossi

Linus's Law

“Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.”

Linus Trovalds

It captures the essence of open-source collaboration, where broad community involvement helps identify and fix bugs more effectively than in closed systems. The idea is that the more people who inspect the code, the higher the likelihood that someone will notice and address bugs that others might miss.

Hofstadter's Law

It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law.

Douglas Hofstadter

Hofstadter's Law serves as a reminder of how consistently inaccurate we tend to be when estimating the time required for tasks, especially in software development.

It reinforces the importance of buffer time and managing expectations.

Image, author: PJ Milani

Kernighan's Law

“Everyone knows that debugging is twice as hard as writing a program in the first place. So if you’re as clever as you can be when you write it, how will you ever debug it?”

Brian Kernighan

Writing too complex code could be dangerous for system maintenance. If the code is written with excessive complexity, debugging becomes even more difficult, since you have to first decipher the logic before fixing any issues. Simplicity in coding is key—writing clear, maintainable code makes it easier to debug and improve in the long run.

Peter Principle

“People in a hierarchy tend to rise to ‘a level of respective incompetence.’”

Laurence Peter

Success often comes with a price. In many cases, individuals are promoted to higher and higher positions based on their achievements. However, there comes a point where the demands of the role may exceed their abilities.

In software, this is frequently seen when successful developers are promoted to managerial positions. The assumption is often made that leadership and soft skills naturally grow alongside technical expertise, but this isn't always true. A skilled coder may not necessarily have the same aptitude for managing people, leading teams, or handling the strategic demands of leadership, which can lead to challenges in their new role.

Image, author: Lotfi Alsouki

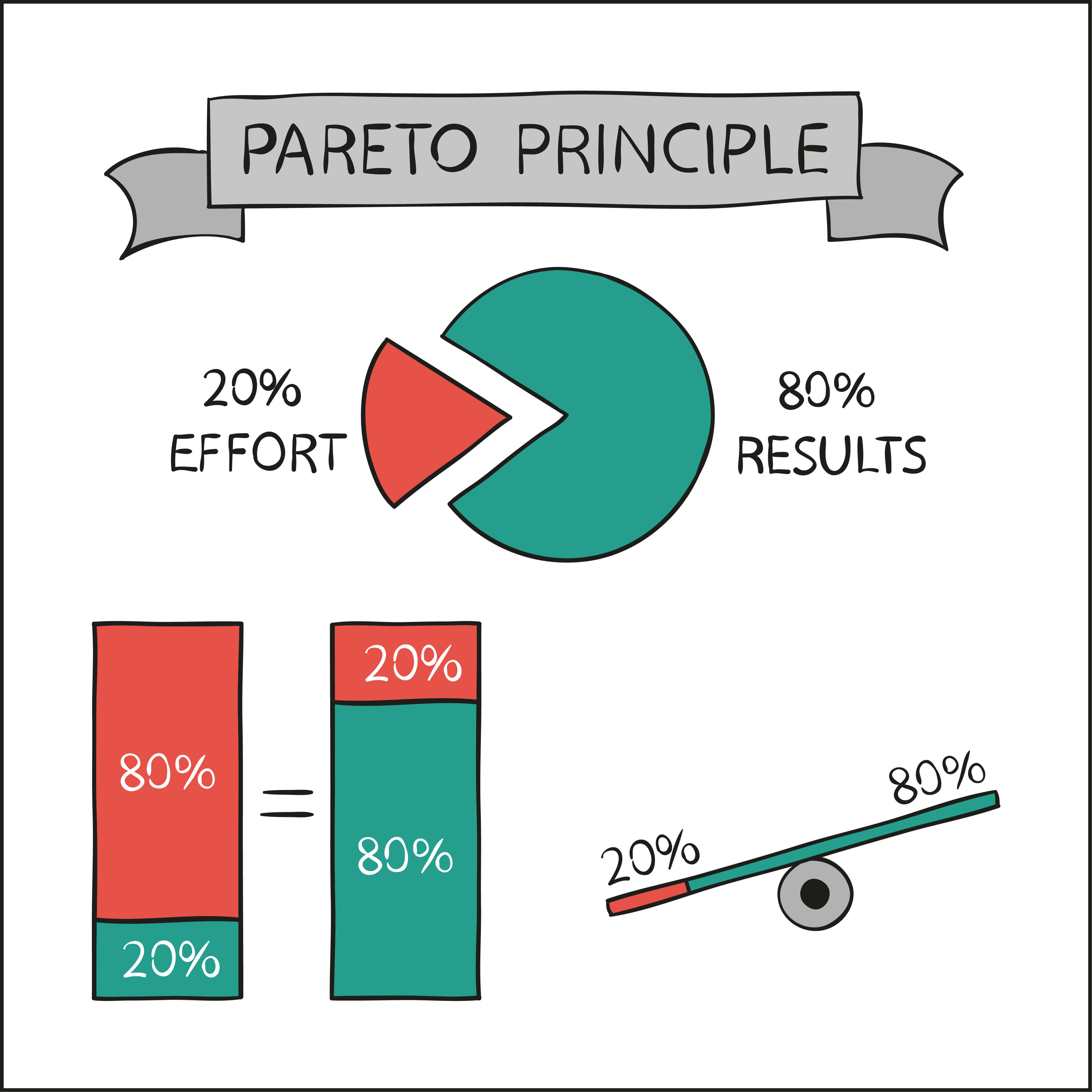

Pareto principle

“For many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes.”

Vilfredo Pareto

The Pareto Principle is widely applicable, and one of its key insights is that effort should be selective. The takeaway is that focusing on the most impactful areas—typically the 20% that yields 80% of the results—leads to greater success than spreading effort too thin. This also emphasizes that quality outweighs quantity and that true outcomes are more important than just the volume of generated output. Prioritizing what truly moves the needle helps achieve more meaningful and sustainable results.