Table of contents

Introduction

Building effective teams are one of the organization's primary concerns. People working in agile methodologies recognize the value of flexibility, continuous collaboration, and development process refinement. However, I would like to demonstrate that agility does not have to embrace change and fluidity in all aspects of software development. In this article, I will discuss several team traits (goal, autonomy, size, longevity, stability) and consider how these things affect team performance. The study of how that qualities are manifested by various team structures (silo team, stream-aligned team, feature team, etc.) is not a part of my analysis. It is a large topic and should probably be the subject of a different article.

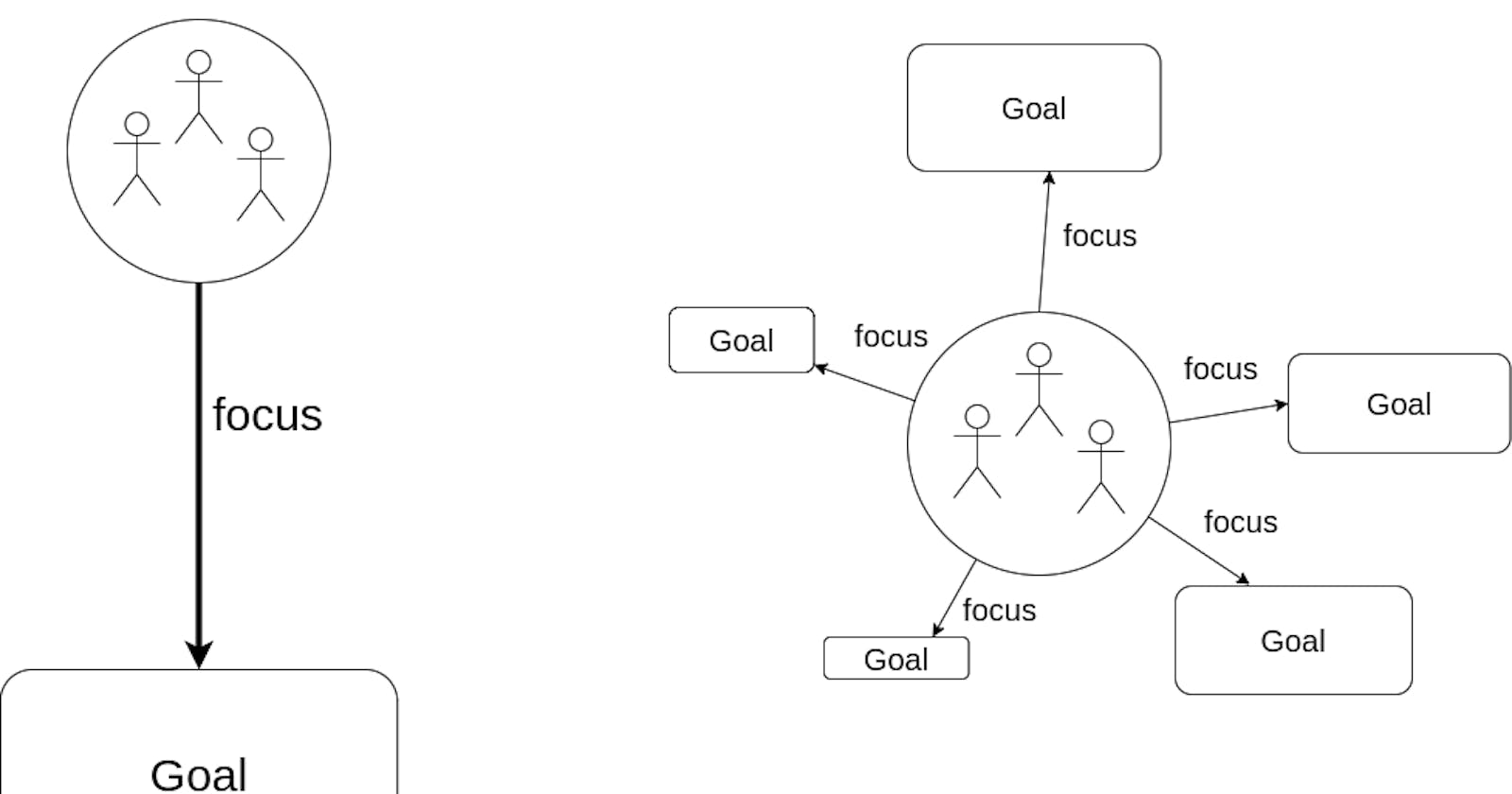

Narrow goal

A software team's goal should be to create high-quality, reliable software that meets the stakeholders' and users' needs. It is hard to disagree with that statement. However, that definition is quite vague and does not pass any signs of strategy that must be taken to achieve it. The lack of precision in goal determination can lead to team members' ambiguous understanding of daily duties (distracted team). In that case, it is really hard to build a team identity and determine what is most crucial for that group of people, and what they are accountable for. Team members that do not have clarity of purpose are vulnerable to excessive context switching. Context switching is a process of frequently changing attention from one task or project to another, or even doing several actions simultaneously. It results in an extraneous cognitive load that weakens our focus and concentration ability. Multitasking can give the impression of being busy and doing many things, but usually, it decreases our productivity and affects the quality of the work output. The remedy for it is setting narrow goals and ensuring that team members have clear sense of purpose to prioritize their tasks (focused team). The team goal should be an integral part of the organization's strategy and be aligned with its objectives.

Autonomy

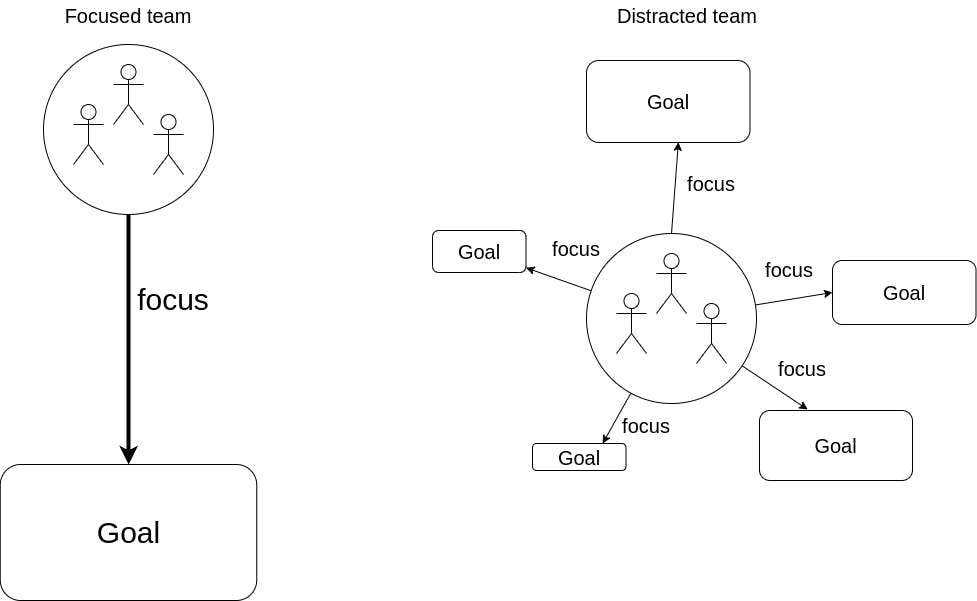

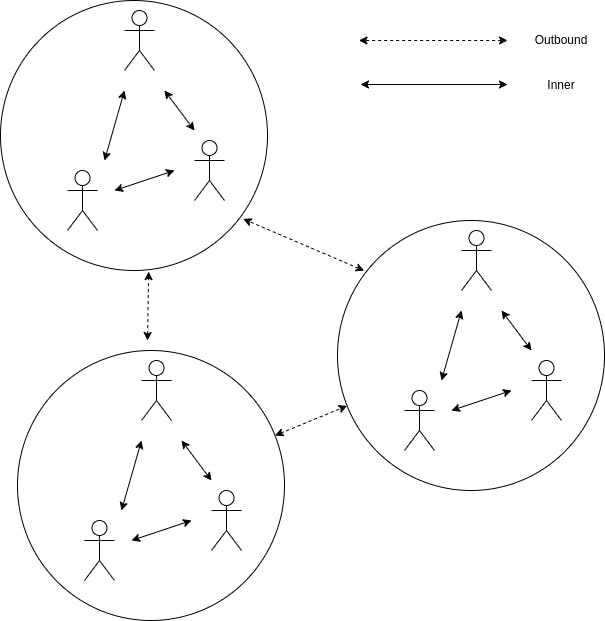

Autonomy is a crucial aspect of a high-performance team. A team that is self-dependent and does not rely on other teams' work, can realize its goal without external blocking and waiting. However, independence has a cost. The team must be cross-functional and have sufficient capable resources to accomplish the goal without excessive outbound communication with people outside the unit.

A cross-functional team is a team that consists of members with different skills, roles, and expertise. For example, the team might include developers, QA engineers, and product managers, who can work together to ensure that the software is well-designed, well-tested, and meets the needs of the users. Assuming that we have a typical software system, here are the primary responsibilities that must be addressed by the cross-functional team:

stakeholders' determination and the identification of their needs

business requirements analysis

frontend system coding

backend system coding

quality assurance and testing (how the system would be tested? when it is ready?)

system architecture design

project management (timing, budget)

User Interface (UI) design

User experience (UX)

CI / CD pipelines

infrastructure maintenance

system monitoring and observability

business intelligence (reporting and business metrics)

team leadership

It is a good idea before a project kick-off to prepare a list of team responsibilities. Having also a potential team squad, we can determine the level of competency of each member in the above fields. How this analysis can look like? For example, we take a team of five members and check how these responsibilities could be allocated:

Bob (DevOps Engineer)

Alice (Product Owner)

Karl (Frontend Developer)

Joe (Backend Developer)

Irin (UX/UI Designer)

The above table shows us that our team can be independent in project development and deliver a system from end to end. Nevertheless, if we find that some fields are unaddressed (visually - the whole raw will be RED), we must add somebody to the team (easier said than done, I know) or make it up that the team is not autonomous and must rely on external resources.

Optimal size

Team size is also an important factor to consider when organizing a software development team. A team that is too large may be difficult to manage and coordinate, while a team that is too small may not have the resources or expertise to complete the project.

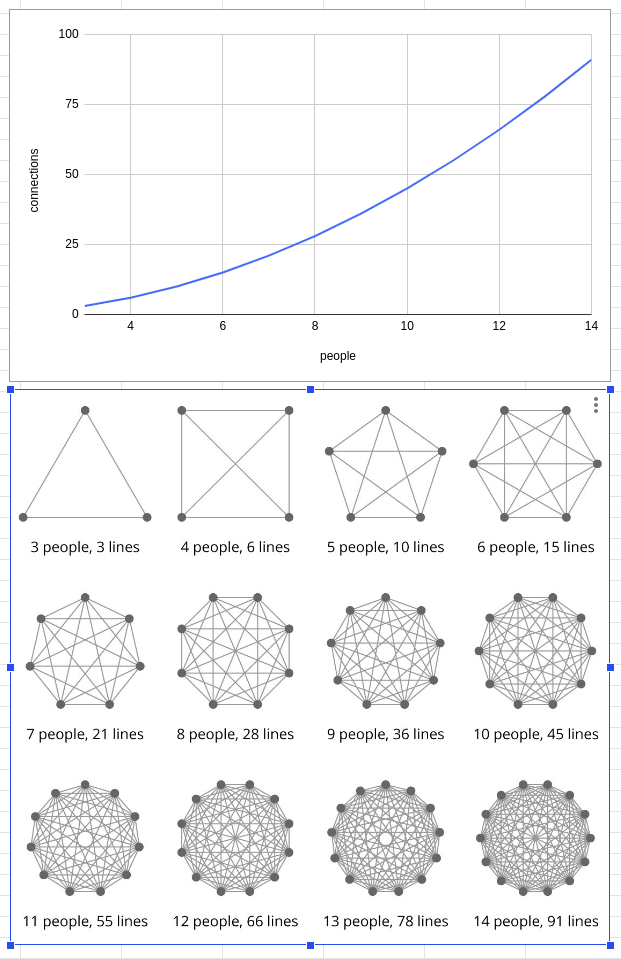

We have seen how many responsibilities must be allocated for the team to be autonomous. Our exemplary analysis also showed that responsibility does not have to be necessarily mapped to a separate team role. It is important to find a balance between a too-large team and a small team consisting of members wearing multiple hats (vulnerable to overutilization and context switching). Why large teams are not a good idea? According to Brooks Law, at some point, the coordination cost of team expansion outweighs the benefits of additional expertise.

source: https://codescene.com/blog/visualize-brooks-law/

This cost mainly comes from extensive communication paths within a team. If we have 3 people, we have only 3 communication paths. For 10 people, we get 45 paths...

source: https://zknill.io/posts/brooks-law-hierarchy-async-comms/

So, for each team, we should find the optimum point of coordination cost and satisfactory competence level. For example, Jason Fried and David Heinemeier Hansson, in their book It doesn't have to be crazy at work, claim that three-people teams (2 developers, and a designer) work best for their company. Matthew Skelton, and Manuel Pais, authors of Team Topologies, believe that the golden number for an agile team is between 5 and 9 people. Depending on your project type and complexity (whether it needs a User Interface, can we use cloud serverless solutions, etc.), and organization culture, the team size would fluctuate and you have to find your optimum.

Longevity

The longevity property tells us how long roughly the same group of people work together. Hao Ji and Jin Yan in their article studied whether team longevity impacts team structure and coordination. They found that long-lived teams can refine a team structure that "can effectively integrate individual work through establishing clear rules, procedure, and roles for team task, then team productivity and efficiency can be elevated". Mature teams have the opportunity to establish daily routines and widely-known conventions over time that make work more predictable and designed. Team longevity enhances previous team traits: understanding of goals and members' responsibilities. However, the team can be long-lived only if it is stable over time.

Stability

Two sources can affect the stability of the team: people inflow and people outflow. We said above that adding new people does not necessarily improve team performance. We cite here another conclusion from Brooks Law Wikipedia page:

It takes some time for the people added to a project to become productive. Brooks calls this the "ramp up" time. Software projects are complex engineering endeavors, and new workers on the project must first become educated about the work that has preceded them; this education requires diverting resources already working on the project, temporarily diminishing their productivity while the new workers are not yet contributing meaningfully. Each new worker also needs to integrate with a team composed of several engineers who must educate the new worker in their area of expertise in the code base, day by day. In addition to reducing the contribution of experienced workers (because of the need to train), new workers may even make negative contributions, for example, if they introduce bugs that move the project further from completion.

Adding new people to the team is usually a cost because rooted team members must sacrifice some of their time to onboard newbies. It also takes some time for a new member to bring value to the team.

While the inflow of people can have both pros and cons, the outflow is rather definitely detrimental to team productivity. The team loses a member that is integrated with the group and probably knows a lot about the project and business domains. Although we cannot stop people from seeking new challenges, we can take care of the proper mixture of personalities in the team. Kim Scott in her inspirational book Radical Condor divides people into two groups:

rocks that enjoy where they are and are happy within their role

superstars that are driven by ambition and need new challenges frequently

Rocks provide stability, while superstars are a source of growth for a team. It is really hard to keep a team stable if the group consists of superstars only. A good team balance needs a mixture of both.

It is also easier to keep people in the team when they like each other, are satisfied with their roles, and have abilities for growth and skills improvement.

Summary

The performance of a software development team can be impacted by a number of important aspects, which are covered in this article. I described the necessity of having clear goals and ensuring that team members have a clear sense of purpose and are able to prioritize their work. In addition, I emphasized the value of cross-functionality that brings autonomy and how team size can impact communication paths. In order to develop a strong team identity, trust, and collaboration among team members, I highlighted the necessity for continuity and longevity in a team.

I am aware that building a team is a complicated process. Even if we know what people we would like to have in a team, it is really difficult to make it happen. The recruitment process is expensive and the competition to lure experienced candidates is huge. Nevertheless, people that are responsible for human resources, should have a clear idea about desired team shape and try to implement it.

Please share your feedback if you have any thoughts or experiences about building a team!