Table of contents

Introduction

Object Relational Mappers (ORMs) are widely used in software development to abstract database operations in our application code by providing a layer between object-oriented programming language and relational tables in a database. However, we should be conscious that simple and inconspicuous expressions provided by our ORM can lead to heavy actions underhood. To present it I will take SQLAlchemy, one of the most popular ORMs in the Python world.

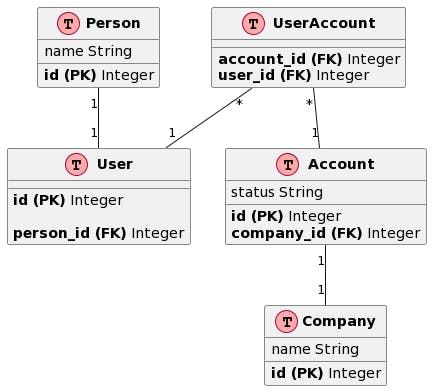

Suppose we have a set of simplified models representing aUser in a Company:

class Person(Base):

__tablename__ = "person"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, autoincrement=True)

name = Column(String)

user = relationship("User", uselist=False)

class User(Base):

__tablename__ = "user"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, autoincrement=True)

person_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey("person.id"))

person = relationship("Person")

my_accounts = relationship("UserAccount")

class Company(Base):

__tablename__ = "company"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, autoincrement=True)

name = Column(String)

class Account(Base):

__tablename__ = "account"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, autoincrement=True)

status = Column(String)

company_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey("company.id"))

company = relationship("Company")

class UserAccount(Base):

__tablename__ = "user_account"

account_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey("account.id"), primary_key=True)

account = relationship("Account")

user_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey("user.id"), primary_key=True)

user = relationship("User")

Query counting

Now we would like to perform a query to get a Person matching provided filters and print Company.name that is corresponding to the retrieved Person object.

with Session() as session:

with DBStatementCounter(session.connection()) as ctr:

person = (

session.query(Person)

.join("user", "my_accounts", "account", "company")

.filter(

Person.name.ilike("test%"),

Account.status.ilike("x%"),

Company.name.ilike("company%"),

).first()

)

if person:

print(person.user.my_accounts[0].account.company.name)

DBStatementCounter is a helper class that counts how many database statements were executed within a given context. Assuming that a Person was found, what number of queries do you expect from the above part of the code?

The correct answer is: 5. Surprised?

One query is explicit:

person = session.query(Person)

.join("user", "my_accounts", "account", "company")

.filter(

Person.name.ilike("test%"),

Account.status.ilike("x%"),

Company.name.ilike("company%"),

).first()

Four remaining queries are implicit:

person.useruser.my_accounts[0]my_accounts[0].accountaccount.company

It results from the default lazy loading strategy of our ORM. When we load the Person object it does not automatically load objects through defined foreign keys. We can see how SQL looks in that case:

SELECT person.id AS person_id, person.name AS person_name

FROM person

JOIN user ON person.id = user.person_id

JOIN user_account ON user.id = user_account.user_id

JOIN account ON account.id = user_account.account_id

JOIN company ON company.id = account.company_id

WHERE lower(person.name) LIKE lower(?) AND lower(account.status) LIKE lower(?) AND lower(company.name) LIKE lower(?)

The query has properly joined tables, however in the SELECT section there are only attributes associated to the person table, so to retrieve column values from joined tables we need another query (or queries).

Eager loading

We can change that behavior by passing to relationship an expression: lazy="joined". However, it seems reasonable to not load all connected tables every time we need only a Person's columns. The better option is to do it on demand when we are sure that columns corresponding to linked tables would be used. In SQLAlchemy we can do it using joinedload function that provides attributes from joined tables in SELECT results.

person = session.query(Person)

.join("user", "my_accounts", "account", "company")

.options(

joinedload("user"),

joinedload("user", "my_accounts"),

joinedload("user", "my_accounts", "account"),

joinedload("user", "my_accounts", "account", "company"),

)

.filter(

Person.name.ilike("test%"),

Account.status.ilike("x%"),

Company.name.ilike("company%"),

).first()

That query results in only one query hitting the database. Great! But, when we look at the SQL statement, there is something weird in it:

SELECT

person.id AS person_id, person.name AS person_name,

company_1.id AS company_1_id, company_1.name AS company_1_name,

account_1.id AS account_1_id, account_1.status AS account_1_status, account_1.company_id AS account_1_company_id, user_account_1.account_id AS user_account_1_account_id, user_account_1.user_id AS user_account_1_user_id,

user_1.id AS user_1_id, user_1.person_id AS user_1_person_id

FROM person

JOIN user ON person.id = user.person_id

JOIN user_account ON user.id = user_account.user_id

JOIN account ON account.id = user_account.account_id

JOIN company ON company.id = account.company_id

LEFT OUTER JOIN user AS user_1 ON person.id = user_1.person_id

LEFT OUTER JOIN user_account AS user_account_1 ON user_1.id = user_account_1.user_id

LEFT OUTER JOIN account AS account_1 ON account_1.id = user_account_1.account_id

LEFT OUTER JOIN company AS company_1 ON company_1.id = account_1.company_id

WHERE lower(person.name) LIKE lower(?) AND lower(account.status) LIKE lower(?) AND lower(company.name) LIKE lower(?)

To get additional attributes we have our tables joined twice... If we do not have many records in the database, this would not be a problem. Otherwise, we can encounter huge performance issues like described here. The solution here is to replace joinedload with contains_eager because joinedload basically should not be used with filtering.

person = session.query(Person)

.join("user", "my_accounts", "account", "company")

.options(

contains_eager("user"),

contains_eager("user", "my_accounts"),

contains_eager("user", "my_accounts", "account"),

contains_eager("user", "my_accounts", "account", "company"),

)

.filter(

Person.name.ilike("test%"),

Account.status.ilike("x%"),

Company.name.ilike("company%"),

).first()

Now we are happy because there is only one database query execution and the SQL statement looks correctly:

SELECT

company.id AS company_id, company.name AS company_name, account.id AS account_id, account.status AS account_status, account.company_id AS account_company_id, user_account.account_id AS user_account_account_id,

user_account.user_id AS user_account_user_id,

user.id AS user_id, user.person_id AS user_person_id,

person.id AS person_id, person.name AS person_name

FROM person

JOIN user ON person.id = user.person_id

JOIN user_account ON user.id = user_account.user_id

JOIN account ON account.id = user_account.account_id

JOIN company ON company.id = account.company_id

WHERE lower(person.name) LIKE lower(?) AND lower(account.status) LIKE lower(?) AND lower(company.name) LIKE lower(?)

Conclusion

This was SQLAlchemy and Python example. However, no matter whether you use Django ORM, Java Hibernate, or .NET Nhibernate, you will encounter the same issues and should take proper decisions about the lazy loading of your objects. So, be careful with your ORM.