Coupling is a concept used in software engineering to define how tight a relationship between system components (classes, modules, subsystems) is. Here you have some definitions:

"Coupling is inter-connection between modules" - youtube.com/watch?v=tMW08JkFrBA

"Loose Coupling is when things that should not be together are not together" - injulkarnilesh.github.io/design-principles/..

"Coupling represents the degree to which a single unit is independent of others" - enterprisecraftsmanship.com/posts/cohesion-..

"Coupling refers to how inextricably linked different aspects of an application are" - deviq.com/principles/single-responsibility-..

Two perspectives

Coupling is strictly connected to the cohesion concept ("togetherness" of a component) and there is a common heuristic for software developers that we should design components that have high cohesion and are loosely coupled. But the question is how can we determine the level of coupling for a given component? The above definitions don't bring a straightforward answer. To answer this question we can divide the coupling concept into two aspects: quantitative and qualitative.

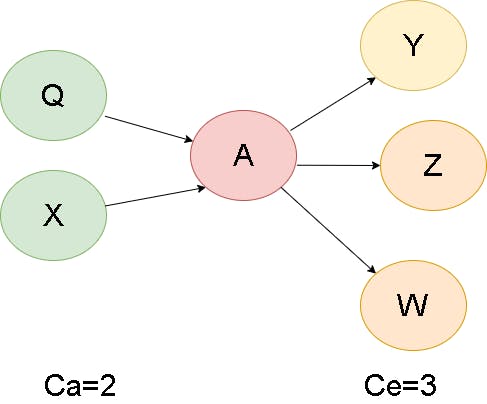

The quantitative perspective refers to the number of dependencies that component A has. It can be represented by two metrics:

Afferent coupling (Ca) - the number of external components that depend on component A.

Efferent coupling (Ce) - the number of external components that component A is dependent on.

The second perspective is qualitative and defines how tight a dependency is between component A and component B. This aspect is often categorized as a type of coupling, like control couping, data coupling, stamp coupling, etc. However, all these types usually are a gradation of knowledge. The more knowledge component A must have about component B to perform action P, the coupling between them is tighter.

Decoupling

As far as the quantitative coupling is concerned, we know what must be done to make coupling looser from that perspective. We should decrease the number of dependencies. But how does decrease qualitative coupling? To present a spectrum of coupling states: from tight to loose, we prepared a set of implementations of a use-case: booking table in a restaurant. There is the main responsibility that is a domain action of booking a table in a system, and the supportive action of sending a notification to a person that booked it. In the following examples, we use also four questions to determine how the implementation of sending notifications is coupled with business action. The questions are:

What supportive action is done? Does my component know which method/function is called?

How the supportive action is done? Does my component know the implementation?

Where the supportive action executor is instantiated? Does my component instantiate executor? Is it a global object? Is it injected?

What is the supportive action executor type? Is it a function? Is it a class or an interface?

The more 'yes' answers to the question: 'do you know it?', the coupling is tighter.

Internal method

class BookingTableService:

def book_table(restaurant_id: str) -> None:

# some implementation

self.send_notification(restaurant_id)

def send_notification(self, restaurant_id: str) -> None:

# some implementation

BookingTableSerice().book_table(1)

(Do we know) What supportive action is done? Yes, we know we a send a notification because we call the

send_notificationmethod.(Do we know) How the supportive action is done? Yes, because we have an implementation of

send_notificationinside our service class.(Do we know) Where the supportive action executor is instantiated? Yes, it is a part of the service class.

(Do we know) What is the supportive action executor type? Yes, yes it is

BookingTableServicetype.

Here we don't have an external dependency, but we put into the same component two different responsibilities. We know everything about sending notifications, so coupling is huge.

Delegation

class NotificationSender:

def send(self, **kwargs)-> None:

# some implementation

class BookingTableService:

def __init__(self):

self._notification_sender = NotificationSender()

def book_table(restaurant_id: str) -> None:

# some implementation

self._notification_sender.send(recruitment_id=recruitment_id)

BookingTableSerice().book_table(1)

(Do we know) What supportive action is done? Yes, we know we send a notification because we call the

NotificationSender.send_notificationmethod.(Do we know) How the supportive action is done? No, because implementation is in the

NotificationSenderclass.(Do we know) Where the supportive action executor is instantiated? Yes, we instantiate in the constructor of the service.

(Do we know) What is the supportive action executor type? Yes, yes it is the

NotificationSendertype.

This is an example of a hidden dependency. We instantiate it inside the service, and it is not represented in the service interface (so not "visible" from outside the component).

Delegation with Dependency Injection

class NotificationSender:

def send(self, **kwargs) -> None:

# some implementation

class BookingTableService:

def __init__(self, notification_sender: NotificationSender):

self._notification_sender = notification_sender

def book_table(restaurant_id: str) -> None:

# some implementation

self._notification_sender.send(recruitment_id=recruitment_id)

BookingTableSerice(notification_sender=NotificationSender()).book_table(1)

(Do we know) What supportive action is done? Yes, we know we send a notification because we call the

NotificationSender.send_notificationmethod.(Do we know) How the supportive action is done? No, because implementation is in

NotificationSenderclass.(Do we know) Where the supportive action executor is instantiated? No, an instance of

NotificationSenderis injected into the service.(Do we know) What is the supportive action executor type? Yes, yes it is the

NotificationSendertype.

Now we know less about the instantiation of a sender and how it is implemented because it is injected into our service. However, we still know what action is done and what is the concrete implementation of the action executor (what, not how).

Delegation with Dependency Injection of Interface

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class NotificationSender(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def send(self, **kwargs) -> None:

pass

class SmsSender(NotificationSender):

def send(self, **kwargs) -> None:

# some implementation

class BookingTableService:

def __init__(self, notification_sender: NotificationSender):

self._notification_sender = notification_sender

def book_table(restaurant_id: str) -> None:

# some implementation

self._notification_sender.send(recruitment_id=recruitment_id)

BookingTableSerice(notification_sender=SmsSender()).book_table(1)

(Do we know) What supportive action is done? Yes, we know we send a notification because we call the

NotificationSender.send_notificationmethod.(Do we know) How the supportive action is done? No, because implementation is in

NotificationSenderclass.(Do we know) Where the supportive action executor is instantiated? No, an instance of

NotificationSenderis injected into the service.(Do we know) What is the supportive action executor type? No, we have only an interface, not a concrete type.

In this approach, we have an interface injected instead of a concrete type. We have defined a contract (interface) for the notification sender and we can take any class that fulfills it.

Event Dispatching

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

from dataclasses import dataclass

from datetime import datetime

from typing import List

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Event:

name: str

originatior_id: str

timestamp: datetime = datetime.now()

class EventHandler:

def handle(self, events: List[Events]) -> None:

for event in events:

if event.name == 'booked_table':

# some implementation of sending notification

class EventDispatcher(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def publish(self, events: List[Event]) -> None:

pass

class LocalEventDispatcher(EventDispatcher):

def publish(self, events: List[Event]) -> None:

handler = EventHandler()

handler.handle(events)

class BookingTableService:

def __init__(self, event_dispatcher: EventDispatcher):

self._event_dispatcher = event_dispatcher

def book_table(restaurant_id: str) -> None:

# some implementation

events = [Event(name="booked_table", originator_id=restaurant_id)]

self._event_dispatcher.publish(events)

BookingTableSerice(event_dispatcher=LocalEventDispatcher()).book_table(1)

(Do we know) What supportive action is done? No, we only dispatch events and do not delegate to send a notification explicitly.

(Do we know) How the supportive action is done? No, because implementation is in

NotificationSenderclass.(Do we know) Where the supportive action executor is instantiated? No, an instance of

NotificationSenderis injected.(Do we know) What is the supportive action executor type? No, we have only an interface, not a concrete type.

Here we have no dependency. We published an event and do not even know whether other component handles it.

| (Do we know) How the supportive action is done? | (Do we know) Where the supportive action executor is instantiated? | (Do we know) What is the supportive action executor type? | (Do we know) What supportive action is done? | |

| Internal method | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Delegation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Delegation with DI | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Delegation with DI interface | No | No | No | Yes |

| Event dispatching | No | No | No | No |

Summary

We have shown some ways of analyzing coupling between two components (responsibilities). However we should be conscious it is not always true that the less coupling, the better. In some cases, we don't need an abstraction (interface), because we have only one implementation. Introducing Dependency Injection with Interface in that case would be overkill. Event dispatching is a great way to decouple several components, but it also introduces some complexity. When we see only publishing events in the part of code (but not see handling it), we lose some sense of causality in our code (what happens next). So you must always choose the optimal solution for your case. Thanks for reading.