Overview

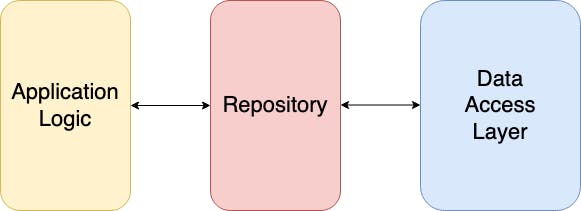

The Repository Pattern is a software design pattern that provides an abstraction layer between the business logic of an application and the persistence layer (typically a database). It helps to separate the concerns and provides a consistent interface to access and manage data.

In the Repository Pattern, a repository acts as a mediator between the application and the data source. It encapsulates the logic for retrieving, storing, and querying data, allowing the application to interact with the repository instead of directly accessing the database or other data sources.

While the repository pattern is commonly associated with Domain-Driven Design (DDD) and Clean Architecture, it is a flexible and versatile pattern that can be used in various software development contexts.

Application core

The main benefit of using a repository pattern is that we can write application code without an assumption about the data provider in front (e.g. filesystem, database, external API). In that scenario, the orchestration of business processes can be tested without integration tests and mocking external dependencies.

For better understanding, we can take an example of a simple application that enables users downloading resources. We would focus on a small part of the business process: registering that a given resource was downloaded if a user has not exceeded the download limit yet.

ResourceDownloader is a domain object that keeps already downloaded resources and the current limit is responsible for enforcing business invariant (the number of downloads for a given user cannot exceed the limit).

type UserId string

type ResourceId string

type ResourceDownloader struct {

UserId UserId `json:"user_id"`

Resources []ResourceId `json:"resources"`

Limit int `json:"limit"`

}

func (d *ResourceDownloader) isLimitReached() bool {

return len(d.Resources) >= d.Limit

}

func (d *ResourceDownloader) RegisterDownload(

resourceId ResourceId

) error {

if d.isLimitReached() {

return fmt.Errorf("limit reached")

}

d.Resources = append(d.Resources, resourceId)

return nil

}

DefaultDownloadService is an application service responsible for orchestrating download registration use case.

There are 4 main steps in the process:

Fetching

ResourceDownloaderinstance usingDownloaderRepository.Getmethod.Delegating to

ResourceDownloaderdownload registration attempt.Performing download of the resource (we skip the implementation of that step to keep the example concise).

Storing

ResourceDownloaderrefreshed data usingDownloaderRepository.Savemethod.

type DownloaderRepository interface {

Get(ctx context.Context, userId UserId) (ResourceDownloader, error)

Save(ctx context.Context, downloader ResourceDownloader) error

}

type DownloadService interface {

DownloadResource(userId downloader.UserId, resourceId downloader.ResourceId) error

}

type DefaultDownloadService struct {

DownloaderRepository downloader.DownloaderRepository

}

func NewDownloadService(downloaderRepository downloader.DownloaderRepository) DefaultDownloadService {

return DefaultDownloadService{

DownloaderRepository: downloaderRepository,

}

}

func (s DefaultDownloadService) DownloadResource(ctx context.Context, userId downloader.UserId, resourceId downloader.ResourceId) error {

resourceDownloader, err := s.DownloaderRepository.Get(ctx, userId)

if err != nil {

return err

}

err = resourceDownloader.RegisterDownload(resourceId)

if err != nil {

return err

}

// Take action to perform the download

err = s.DownloaderRepository.Save(ctx, resourceDownloader)

if err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

As you can see DefaultDownloadService is dependent on DownloaderRepository class. However, DownloaderRepository is an interface that does not reveal the implementation details. As a result, our application service does not have any knowledge about infrastructure components.

The interface of DownloaderRepository is simple and consist of two methods:

Getto retrieve an object from the datasourceSaveto store an object in the datasource

Repository implementations

In-memory

Now we can provide some DownloaderRepository implementations. The most straightforward option is in-memory storage. We use a simple map that has UserId as a key and ResourceDownloader instance as a value to store information about downloaded resources and the limit for a user.

type InMemoryDownloaderRepository struct {

Storage map[downloader.UserId]downloader.ResourceDownloader

}

var _ downloader.DownloaderRepository = (*InMemoryDownloaderRepository)(nil)

func NewInMemoryDownloaderRepository() InMemoryDownloaderRepository {

return InMemoryDownloaderRepository{

Storage: make(map[downloader.UserId]downloader.ResourceDownloader),

}

}

func (r InMemoryDownloaderRepository) Get(ctx context.Context, userId downloader.UserId) (downloader.ResourceDownloader, error) {

resourceDownloader, ok := r.Storage[userId]

if !ok {

return downloader.ResourceDownloader{}, fmt.Errorf("downloader not found")

}

return resourceDownloader, nil

}

func (r InMemoryDownloaderRepository) Save(ctx context.Context, resourceDownloader downloader.ResourceDownloader) error {

r.Storage[resourceDownloader.UserId] = resourceDownloader

return nil

}

Although that implementation should not be used in production systems, it is a great building block for business use cases testing (without using mocks).

import "github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

func TestDownloadService(t *testing.T) {

repository := inmemory.NewInMemoryDownloaderRepository()

userId := downloader.UserId("user1")

resourceDownloader := downloader.NewResourceDownloader(

userId, []downloader.ResourceId{}, 5

)

repository.Save(context.Background(), *resourceDownloader)

service := NewDownloadService(repository)

err := service.DownloadResource(

context.Background(), userId, "resource1"

)

assert.NoError(t, err)

resourceDownloaderFromRepo, _ := repository.Get(

context.Background(), userId

)

assert.NoError(t, err)

assert.Equal(

t,

[]downloader.ResourceId{"resource1"},

resourceDownloaderFromRepo.Resources,

)

Redis

Redis is an open-source, in-memory data structure store that can be used as a database, cache, and message broker. Redis is designed for high-performance data storage and retrieval, offering low-latency access to data. Our Redis implementation of the repository pattern keeps JSON-encoded ResoruceDownloader object under key name generated by a function generateDownloaderKey.

import "github.com/redis/go-redis/v9"

type RedisDownloaderRepository struct {

client *redis.Client

}

func NewRedisDownloaderRepository(client *redis.Client) RedisDownloaderRepository {

return RedisDownloaderRepository{client: client}

}

var _ downloader.DownloaderRepository = (*RedisDownloaderRepository)(nil)

func (r RedisDownloaderRepository) Get(ctx context.Context, userId downloader.UserId) (downloader.ResourceDownloader, error) {

result, err := r.client.Get(ctx, generateDownloaderKey(userId)).Result()

if err == redis.Nil {

return downloader.ResourceDownloader{}, fmt.Errorf("downloader not found")

} else if err != nil {

return downloader.ResourceDownloader{}, err

}

var resourceDownloader downloader.ResourceDownloader

err = json.Unmarshal([]byte(result), &resourceDownloader)

if err != nil {

return downloader.ResourceDownloader{}, err

}

return resourceDownloader, nil

}

func (r RedisDownloaderRepository) Save(ctx context.Context, resourceDownloader downloader.ResourceDownloader) error {

resourceDownloaderJSON, err := json.Marshal(resourceDownloader)

if err != nil {

return err

}

err = r.client.Set(ctx, generateDownloaderKey(resourceDownloader.UserId), resourceDownloaderJSON, 0).Err()

if err != nil {

return err

}

return nil

}

func generateDownloaderKey(userId downloader.UserId) string {

return fmt.Sprintf("downloader:%s", userId)

}

In cases where you are using a data store like Redis, which does not provide transactional guarantees, there is a possibility of stale data if changes are made to the data outside the context of the repository. You can mitigate that behavior by using optimistic or pessimistic locking approaches (see more here about it). Atomic operations are also supported in Redis by using Lua scripts. However, the Lua scripts utilization would exclude the possibility of repository pattern implementation.

External API with cache

Repository pattern is not restricted only to databases and filesystems. In distributed system repository pattern can be exploited as an abstraction for an external REST API data source. In the following example, we set up CachedExternalDownloaderRepository class. If the ResourceDownloader object is not found in the cache, the repository will make a call to the External User Service API (using UserServiceClient) that keeps information about downloads limits for users. The data fetched from User Service is returned by CachedExternalDownloaderRepository and also stored in the local cache for subsequent requests.

type CachedExternalDownloaderRepository struct {

cache downloader.DownloaderRepository

client UserServiceClient

}

var _ downloader.DownloaderRepository = (*CachedExternalDownloaderRepository)(nil)

func NewCachedExternalDownloaderRepository(

client UserServiceClient, cache downloader.DownloaderRepository

) CachedExternalDownloaderRepository {

return CachedExternalDownloaderRepository{

cache: cache,

client: client,

}

}

func (r CachedExternalDownloaderRepository) Get(ctx context.Context, userId downloader.UserId) (downloader.ResourceDownloader, error) {

resourceDownloaderFromCache, err := r.cache.Get(ctx, userId)

if err == nil {

return resourceDownloaderFromCache, nil

}

userLimit, err := r.fetchUserLimitsFromExternalAPI(ctx, userId)

if err != nil {

return downloader.ResourceDownloader{}, err

}

resourceDownloader := downloader.NewResourceDownloader(

userId, []downloader.ResourceId{}, userLimit.Limit

)

_ = r.cache.Save(ctx, *resourceDownloader)

return *resourceDownloader, nil

}

func (r CachedExternalDownloaderRepository) Save(

ctx context.Context, resourceDownloader downloader.ResourceDownloader

) error {

return r.cache.Save(ctx, resourceDownloader)

}

func (r CachedExternalDownloaderRepository) fetchUserLimitsFromExternalAPI(

ctx context.Context, userId downloader.UserId

) (UserLimit, error) {

userLimit, err := r.client.Get(ctx, userId)

if err != nil {

return UserLimit{}, err

}

return userLimit, nil

}

type UserLimit struct {

UserId downloader.UserId `json:"user_id"`

Limit int `json:"limit"`

}

type UserServiceClient interface {

Get(ctx context.Context, userId downloader.UserId) (UserLimit, error)

}

type DefaultUserServiceClient struct {

baseURL string

}

func NewDefaultUserServiceClient(baseURL string) DefaultUserServiceClient {

return DefaultUserServiceClient{baseURL: baseURL}

}

func (c *DefaultUserServiceClient) Get(

ctx context.Context, userId downloader.UserId

) (UserLimit, error) {

url := fmt.Sprintf("%s/users/%s", c.baseURL, userId)

response, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

return UserLimit{}, err

}

defer response.Body.Close()

if response.StatusCode != http.StatusOK {

return UserLimit{}, fmt.Errorf("failed to get user with ID %s", userId)

}

body, err := ioutil.ReadAll(response.Body)

if err != nil {

return UserLimit{}, err

}

var userLimit UserLimit

err = json.Unmarshal(body, &userLimit)

if err != nil {

return UserLimit{}, err

}

return userLimit, nil

}

This approach allows you to leverage a local cache to minimize the number of external API calls and improve the performance of your application. The cache acts as a layer between the repository and the external API, providing a faster data retrieval option when the data is already available locally. The cache is represented also by DownloaderRepository and we can use In-memory or Redis implementation for it.

import "github.com/redis/go-redis/v9"

redisClient := redis.NewClient(&redis.Options{

Addr: "localhost:6379",

Password: "secret",

DB: 0,

})

cache := internalRedis.NewRedisDownloaderRepository(redisClient)

userServiceClient := external.NewDefaultUserServiceClient(

"http://localhost"

)

external.NewCachedExternalDownloaderRepository(

&userServiceClient, cache,

)

Conclusion

The repository pattern provides a way to abstract and encapsulates the data access logic, separating it from the business logic and promoting a more modular and testable codebase. It helps to decouple the application from the specific details of the underlying data storage or persistence mechanism.

In this post, we presented In-memory, Redis, and External API with cache implementations. Nevertheless, the presented approach is extensible and we can easily add a filesystem or RDBS (e.g. PostgreSQL) as a data provider.

The full implementation of the above example with tests can be found in the GitHub repo.